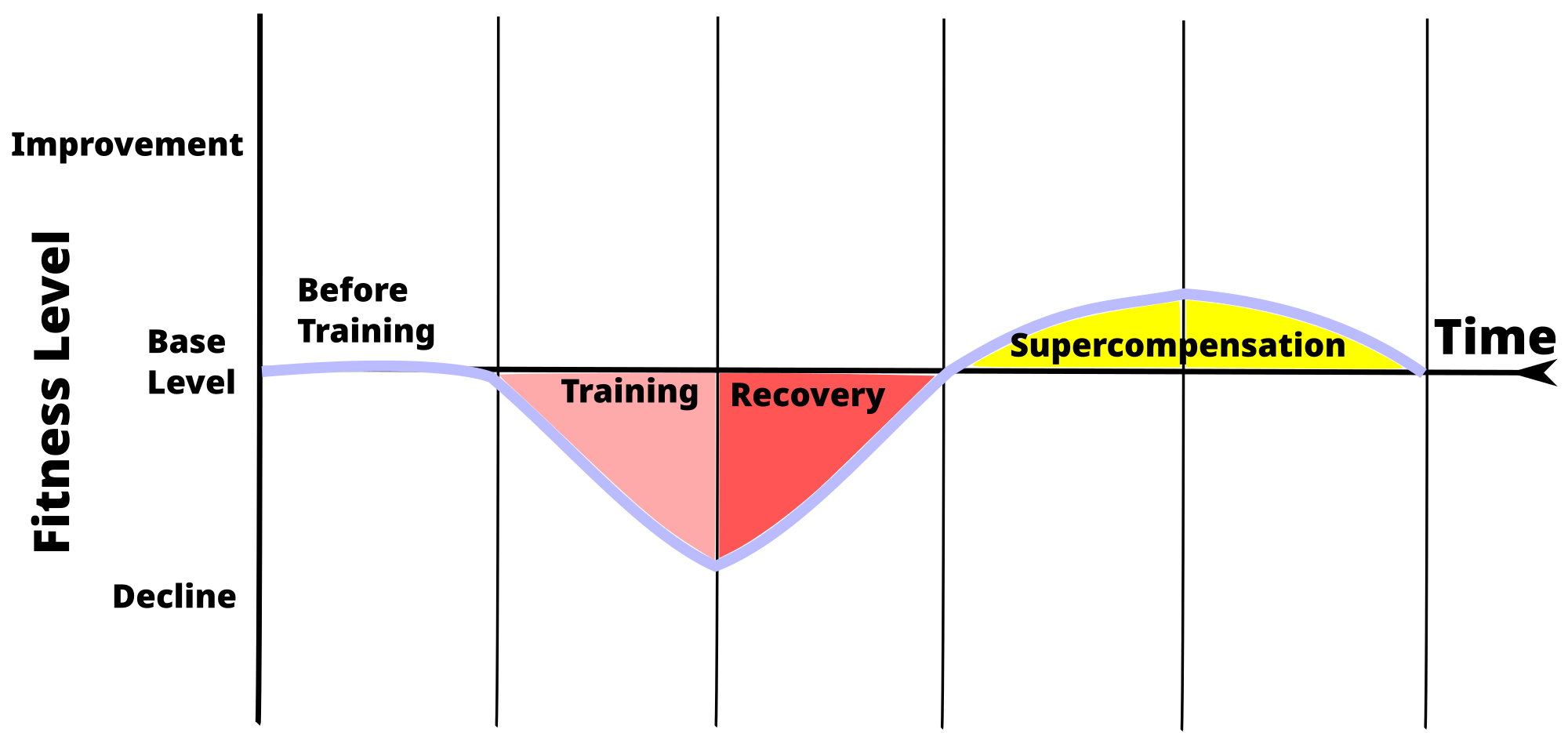

Let's take a look at this nice graph that I stole from the internet for a second.

At the bottom, the red valley caused from weeks of hard training, is a drop in performance, a drop in testosterone, an increase in blood cortisol, irritability, fatigue, sleep disruptions, and other nasty things depending how long and how intense the training block is.

At the bottom, the red valley caused from weeks of hard training, is a drop in performance, a drop in testosterone, an increase in blood cortisol, irritability, fatigue, sleep disruptions, and other nasty things depending how long and how intense the training block is.I've spent too much time in this block over my career. A lot of athletes have this problem, not taking the time to come out of that fatigue. So it never goes away and they never get to truly bask in the mustard coloured glory of the supercompensation curve.

Down, up, down, up, down, up.

It seems so simple, but I've seen a trend in athletes (like myself) who self-program and want peak performance as soon as possible. It becomes all about the training block and the recovery block gets completely ignored even though it's MORE IMPORTANT. That sounds cliche but it's true. The body only makes new tissue when it's resting.

If there isn't a consistent improvement in performance, something isn't working.

But isn't it more of an art than a science? Too much training, and it's impossible to recover enough to see an increase in performance without losing fitness, and not enough training and there won't be enough stimulus to improve.

Something I've been interested in this week and has caused me to wipe out the ol' exercise physiology textbook is the different kinds of fatigue athletes face.

1. Local fatigue

2. Neural Fatigue

3. Endocrine Fatigue

Local fatigue, the fatigue of a specific muscle or tissue in the body, seems to be negligible at a certain point. Well, not negligible, but if the athlete is good at monitoring their body, a lot of injuries can be avoided by reducing volume/dropping painful exercises. Obviously in high level athletes there's a lot of pushing the boundaries, but the old adage, don't train through pain, seems to be the best advice.

Neural fatigue, is something that every power/strength athlete must be familiar with. Do a 1RM squat and try to do the same thing the next day. Not happening. This has always been the type of fatigue I've been concerned with. If the nervous system doesn't have time to recover, there will be a continuous drop in performance. "But I lifted this week last week..."

Endocrine fatigue is something I've really only given thought to over the last few weeks. Things like Testosterone to cortisol levels which go down during high blocks of training and improve during the recovery phase. This is something I've suffered from when I haven't taken enough time to recover. It can be maddening, having the desire to get back on the track or gym but being too tired to get out of bed. Headaches, lethargy, spaciness. It's definitely not a fun experience.

At some points in my career, I thought I might have had "Adrenal fatigue" which was supposedly when your kidneys get so burned out that they stop producing cortisol.

Adrenal fatigue DOES NOT EXIST. That doesn't mean you can go crazy and beat yourself down seven days a week. You'll feel like crap because of high cortisol levels and neural fatigue, but as of now, there is no research that supports the idea that stressing the adrenal glands can cause permanent malfunction. Here's a link with more. Or do a quick google search. I dare you to find one peer reviewed study stating otherwise.

https://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/fatigued-by-a-fake-disease/

The take home message is there are times when being fatigued is okay and necessary.

No fatigue = no gainz.

But it's important not to get so beat down that it's impossible to recover by the end of the training block. For example. After a three or four week speed block, if the athlete is running slower than they started, it probably means they didn't spend enough time recovering. If there's no change, they probably didn't work hard enough to cause a training effect.

Some ways that I've been measuring my day to day condition are:

- Taking heart rate every morning (an increase of more than 8 beats per minute is linked to training stress)

- Self reporting how I feel on a scale to 1-10 when I wake up

- Self reporting how I feel during the workout on a scale to 1-10

- Tap-test: This is something I'm experimenting with. It's thought that there is a correlation between the number of times you can tap your finger with your level of neural fatigue. I use an app that counts taps per 30 seconds but haven't been doing it long enough to say how effective it is. There might also be a learning effect that could skew the data.

In the future, I would also like to experiment with testing testosterone and cortisol levels in my blood. This isn't something I feel is necessary for high level performance, as self-monitoring is probably good enough for most athletes, but it may worth checking for long term endocrine stress.

No comments:

Post a Comment